Portland Copwatch

a project of Peace and Justice Works

PO Box 42456

Portland, OR 97242

(503) 236-3065/ Incident Report Line (503) 321-5120

e-mail: copwatch@portlandcopwatch.org

"Independent" Police Review 2020 Annual Report:

Inadequate Reporting Continues on Force, Discipline

an analysis by Portland Copwatch June 28, 2021

On June 3, the "Independent" Police Review (IPR) released its 2020 Annual Report, a seven page document with six pages of appendices.*-1 While the new report brought back some information from the 2018 version missing in 2019's five-page Report, it continues to lack adequate reporting on force (and contains nothing about deadly force), discipline, community members' role in oversight, and even their own outreach program. Most problematic: in a year of protests sparked by a racist police murder in Minneapolis, there is barely any mention of race. Below is Portland Copwatch (PCW)'s analysis of the report, which includes some data gleaned from IPR's website and other data regularly tracked by PCW (indicated with a"+x"). As PCW noted in last year's analysis, "the paid IPR staff should relay information to the community in a thorough and transparent way, rather than making community members jump through extra hoops to find data." Moreover, while the IPR acknowledges they fell behind in complying with the 180 day deadline to finish investigations required by the US Department of Justice (DOJ) Settlement Agreement, they once again made no reference at all to police treatment of people with mental illness-- the main focus of the DOJ's investigation.

In its early years, IPR put out annual reports that were over 100 pages long, filled with tables and charts. Later those were whittled down to reasonably sized 30-ish page reports with similar information in smaller packages. In recent years, the reports have all been fewer than 20 pages, more heavily dominated by infographics than data and analysis.

Notably, the scant data that IPR did include in the body of the report mostly focus solely on the protest-related complaints, saying how the cases were processed or dismissed, but not the outcomes. PCW feels a thorough analysis of complaints, outcomes and the overall process are crucial as a way to compare IPR to the soon-to-be-implemented oversight system placed into the City Charter by voters as measure 26-217 in November 2020.

Highlights of our analysis:

--there were zero officers found out of policy in 2020 for Use of Force allegations, despite the Portland Police Bureau (PPB) using force over 6000 times and over 222 Force misconduct allegations being filed.+x

---the overall rate for sustaining Force allegations since IPR began in 2002 is 1.2%, with just 29 sustained findings out of 2495 allegations.+x

--because IPR started breaking Force allegations into subcategories a few years ago, they dropped out of the top five most common allegations. However, since it constitutes three of the top 10 categories, Force was the #1 allegation type in 2020.+x

--there were two officer-involved shootings in 2020, both nonfatal, and yet the average number of deadly force incidents per year remains at five.+x

Here are other items which used to be part of IPR Annual Reports which are no longer included:

--a list of the most common types of allegations;

--the exact number of complaints relating to Force and other categories (such as Policy or

Procedure);

--the number of findings other than "Sustained" (out of policy), now shown only as percentages;

--a link to the annual outside consultant's report on deadly force incidents (which IPR contracts and

publishes);

--the number of commendations received for officers; and

--how many investigations were done by Internal Affairs versus those conducted by IPR.

It is important to note that the data PCW presents below are based where possible on the new Annual Report, in part on past Reports and our own analyses of them, and in part on IPR's online dashboard, which is updated at least quarterly basis. Thus, the online numbers may or may not match those used to generate IPR's Report. This is one reason PCW continues to ask IPR to include data tables along with the Annual Reports, so that the numbers are clear when one compares one year to another.

SUSTAIN RATES/FORCE ALLEGATIONS: JUST OVER 1% UPHELD

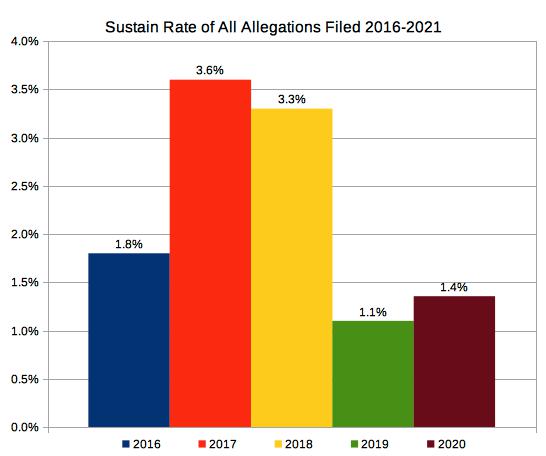

Low Sustain Rate: IPR claims a 5% sustain rate for all allegations, citing 10 findings of "Sustained" among 221 allegations investigated. However, PCW's annual analysis looks at how many misconduct claims were received rather than those investigated. In 2020 it was 10 of 738, or 1.4%. +x The previous sustain rates by PCW's calculations were 1.8% in 2016, 3.6% in 2017, 3.3% in 2018 and 1.1% in 2019. It's not clear why these numbers are so low. If it is because many protest- related allegations were hard to prove, there is no way to know since the Annual Report, the IPR Director's monthly reports, and the online reporting on protest complaints all do not reveal the outcomes of those investigations. See our chart at https://www.pjw.info/copwatch/IPR_annual2020/sustain_rate2020.jpg.

Force Sustain Rate: As noted above, of 222 Force allegations (according to appendix page 2), none were sustained. Since 2002, officers were only found out of policy for Use of Force 29 times, making a 1.2% sustain rate for those allegations divided over 2495 filed.+x That overall average is slightly lower than this year's overall sustain rate of 1.4%, but considerably lower than the five year average of 2.2% for all allegations.+x Notably the Force sustain rate went up since we last reported on it because IPR's dashboard now includes seven sustained findings in 2016, previously reported as just one.+x

What's the Total Number? The figure of 222 Force allegations comes from page 2 of the appendix. However, the IPR's online dashboard gives that number as 156, and adding up the various types of Force allegations (hands/feet=50, "other force"=38, impact munition=18, point firearm=15, strike with instrument=10, takedown=6, chemical use=5, restraints=3, reporting=2 and firearm use=2), there are only 149.+x This is an example of how frustrating it can be to determine what actually happened.

Compare This To Overall Use of Force: The Bureau puts out Quarterly Force Reports saying how many times officers used force.*-2 In the past, PCW compared the number of cases to the number of complaints to estimate how many people filed complaints versus how many were subjected to force. That number was 9% in 2019 and 13% in 2016. This year PCW is adding the number of non-protest cases (639) to the number of protest applications of force (6463), seeing as the Bureau admits the protest number is likely an undercount. (Officers either didn't know how many people they subjected to force or didn't know how many times they used force if it was a repeated action.) Thus, of 7102 incidents involving force, using the Bureau's 222 allegations figure, the percentage of those generating complaints in 2020 was 3%.+x PCW hopes there will be less force used in 2021 to see whether that suspiciously low rate continues.

Why Force Complaints Were Dismissed: IPR identifies why 41 protest-related allegations were dropped (p. 3) and why all kinds of complaints were closed (given as percentages, not numbers, on p. 4 of the appendix). However, after the DOJ Agreement went into effect, Force allegations are all supposed to be investigated unless there is "clear and convincing evidence" not to do so. In 2018, 29 allegations were dismissed for other reasons (see our 2018 analysis). In 2020, 25 Force allegations were not investigated, again none for the reason DOJ allows. Nine were due to the complainant being unavailable, eight were because the complainant had "another remedy" (which PCW continues to find is not consistent with the DOJ Agreement or community expectations), seven were because no misconduct was alleged and in one case the officer could not be identified. This is 11% of the 222 allegations, down from about 30% in 2018.+x

Deadly Force: Where Is It?: IPR is involved in deadly force incident investigations. They send investigators out to observe the scene post-shooting, monitor the investigation, vote at the Police Review Board hearing, and maintain a dashboard showing the location and number of incidents per year. They also contract with an outside consultant, which since 2010 has been the OIR Group from California, to analyze each incident for training, policy and investigation shortcomings. The IPR notes that the protests in Portland in 2020 were "sparked by the murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis" (p. 1), but does not mention anything about the Portland Police Bureau's use of deadly force. The Report also does not mention the two incidents in 2020 in which officers shot at suspects but missed, and as noted above, IPR failed to note publication of the OIR Report in November-- a report IPR pays for and releases to the public. This is the third year in a row the consultants' report was omitted.

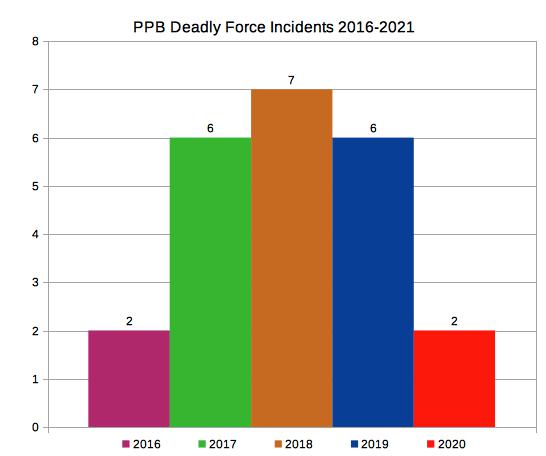

For the record, here are the annual data for deadly force incidents over the last five years, also reflected in our chart at https://www.pjw.info/copwatch/IPR_annual2020/deadly_force2020.jpg :

2016-2

2017-6

2018-7

2019-6

2020-2

The total of 23 incidents means the average of 5 shootings/deaths a year (which went up from 4 between 2017 and 2018) remains the same.+x

Further Deadly Force Follies: City Code section 3.21.070 (L) requires IPR and its Citizen Review Committee (CRC) to follow up on issues raised by the annual deadly force analyses, but neither group has done so since a CRC work group analyzed work by the previous consultants, the Police Assessment Resource Center, in 2010.

What Allegations Were Sustained?: Although no Force allegations were Sustained in 2020, the dashboard only accounts for four of the 10 reported Sustained allegations-- three Procedure and one Conduct. None of the 42 community allegations investigated by IPR in 2020 were Sustained.

MOST COMMON ALLEGATIONS: FORCE , INACTION AND RUDENESS

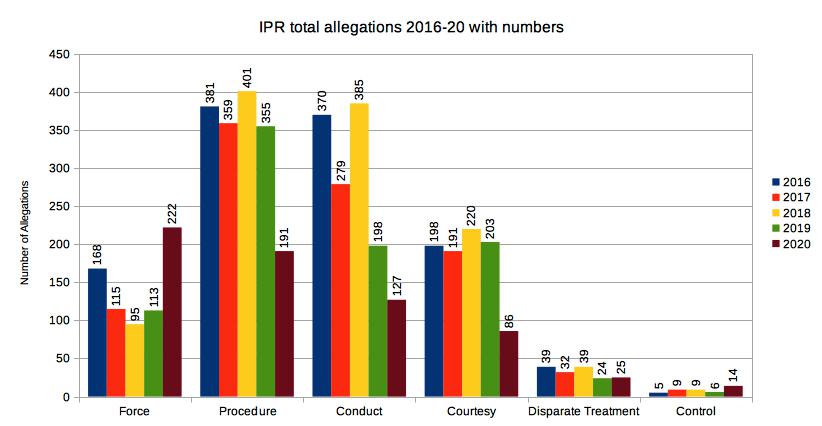

General, Not Specific: The Report shows a five year trend of the types of allegations in six broad categories. As was the case in the 2018 report, the exact number of Force, Procedure, Conduct, Courtesy, Disparate Treatment and Control allegations is hard to determine as the included chart has a numeric grade 0 to 450 but each individual bar is not labeled (appendix p. 2). IPR does note that the 222 Force allegations are nearly double the 112 received in 2019 (though the dashboard puts that number at 113). The 2020 numbers are Force: 222, Procedure: 191, Conduct: 127, Courtesy: 96, Disparate Treatment: 25, and Control: 14. Portland Copwatch has assembled those data properly in a chart that can be found at https://www.pjw.info/copwatch/IPR_annual2020/allegations2020.jpg .+x

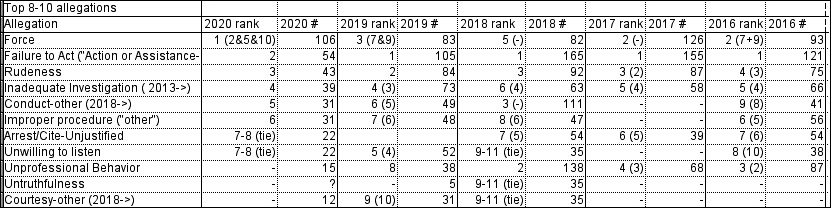

Most Common: Over the years, IPR has changed how they classify certain allegations, most significantly by breaking down Force into smaller categories, whereas originally it was the number 2, 3 or 4 category from 2002-2015 as a broad umbrella. According to the IPR's dashboard, these were the top five allegations in 2020, although for a sense of continuity from the prior years, PCW has combined the top three Force categories which were the #2, 5 and 10 spots, making Force #1 even counting just 110 of the 222 allegations.

#1--Force-Hands/Feet/Knees -50 + Other Force -38 + Impact Munitions -18 = 106 (#3 in 2019)

#2--Inadequate Action or Assistance-54 (#1 in 2019, #1 or 2 for every year since 2009).

#3--Rudeness-43 (#2 in 2019 and #1, 2 or 3 every year 2002-2020).

#4--Inadequate or Improper Investigation-39 (#4 in 2019, #3 to #6 every year 2013-2020).

#5--Other Conduct-31 (#6 in 2019)+x

PCW has posted a list for the last 5 years (2016-2021) at

https://www.pjw.info/copwatch/IPR_annual2020/top10allegations2020.jpg

RACIAL DISPARITIES-- POINTED OUT BY PORTLAND COPWATCH, NOT IPR

IPR Touches on Race: To be fair, IPR raises the issue of racial disparities in four places in their report. They link readers to the investigation of Portland Police officers involved in the arrest of Michael Fesser part of "a racially based retaliation scheme by West Linn [Police]" (p. 6). IPR also says they are analyzing traffic/pedestrian stop and force data along with the allegations made about Disparate Treatment (also p. 6). Then on page 2 of the appendix, the chart of allegations (referenced in Most Common Allegations, above), it shows there were under 50 allegations of Disparate Treatment in 2020 (for the record, it was 25). Most noteworthy is the first reference on p. 2 which contexutalizes the protests in 2020 saying "Racism and disparate enforcement are closely tied to the origins of policing in America, and their legacy extends beyond the behavior of individual officers."

What's Missing 1-Outcomes: IPR doesn't use the opportunity to expand on this observation by analyzing or publishing their own data on racial profiling. They don't note, as Portland Copwatch has repeatedly, that there has only been one Sustained finding of Disparate Treatment in a community complaint since IPR was founded in 2002 (it was in 2007).+x

What's Missing 2-Complaint Sources: IPR previously published data

tables in their reports about who is filing complaints. In 2018 they

noted that African Americans complained at four times their

representation in the population. No data were included in 2019 or 2020.

The online dashboard, however, shows that of 153 291

people who gave their race (just 45% of complainants), 34, or 22% were

Black. This is just below the five year average of 23%.+x Latinx

complainants continued to be far below the 10% of the population one

would expect, with 13 complaints in 2019 and 11 in 2020 (5% and 7% of

known complainants, respectively).+x In a year that even IPR recognizes

was focused on racial injustice, it is not clear why these data aren't

part of the Report.

HOW MANY COPS/ HOW MANY COMPLAINTS

Complaints Down in Busy Year: IPR expresses concern about being overwhelmed by the number of protest-related complaints that were filed in 2020, indeed only focusing on those complaints in the data on pages 2-3, never giving a picture of non-protest complaints. A graphic on p . 3 purports to show the number of protest-related complaints but is actually about _allegations_, showing that of the 738 allegations received, 184 were about protests. The text says those came from 118 complaints. But overall, the number of complaints was down from 409 to 335 (appendix p. 1). It is likely this is related to the police responding to far fewer calls during the pandemic than in other years. The Bureau's open data portal ( https://www.portlandoregon.gov/police/76454) shows officers were dispatched to just 15,099 calls in 2020, a dip of 16% from the 17,918 in 2019; this is similar to the 18% drop in complaints.+x

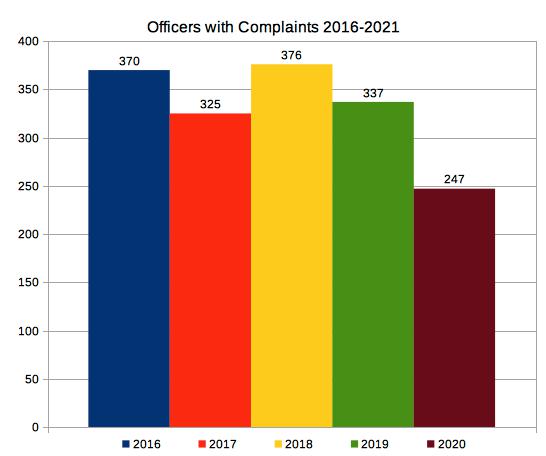

Number of Officers, Five Year Trend: The new Report states that there were complaints filed about 247 officers in 2020, saying this was fewer than 337 in 2019. The latter number is important since this information was not in the 2019 Report and is not part of the dashboard. Previous numbers showed there were 370 officers complained about in 2016, 325 in 2017 and 376 in 2018.+x See a visual comparison at https://www.pjw.info/copwatch/IPR_annual2020/officers_with_complaints2020.jpg .

Cops with Multiple Complaints: While the number of officers with only one complaint about them is about average at 66%, IPR correctly notes that an unusual number of officers had high numbers of complaints against them: two with 6, one with 7 and one with 8. One officer had six complaints in 2018, none had more than five in 2017 or 2019. In our 2018 analysis we noted that from 2011- 2016 only four officers total had six complaints against them.

WHO INVESTIGATED WHAT?

IPR or Internal Affairs?: As noted above, the Report doesn't clearly distinguish what cases were investigated by IPR as opposed to the Bureau's Internal Affairs division (IA). The infographic on p. 2 says IPR conducted 37 investigations. On page 3, it indicates that 25 of those were protest-related cases, while 48 such cases were processed by IA. Though not explicitly stated in the Report, IPR normally investigates protest complaints, but apparently handed off 66% of them to IA due to IPR being overwhelmed. Page 4 of the appendix states that "IPR and Internal Affairs completed 91 investigations into community member complaints in 2020," but doesn't break down which agency did how many.

Why IPR Investigates: The IPR Director sends monthly reports to the CRC showing its ongoing caseload, but never explains the reasons they are investigating complaints instead of IA. In addition to protest complaints, their protocols prioritize Disparate Treatment, complaints when the officer's rank is Captain or higher, certain Use of Force and Retaliation cases, and some at the discretion of IPR or the Mayor. From 2016-2018, data were included in the Annual Report showing why IPR investigated certain cases. Cumulatively in those three years, 23 were about protests, 22 on Disparate Treatment, 16 about Captain or higher, 8 at Director's Discretion, 3 about Force, one Retaliation and one from the Mayor. New data are not in the 2019 or 2020 Reports and not available on the dashboards, which separate complaints and allegations into two separate places but do not give outsiders the ability to see which complaints were handled by IPR. PCW strongly suggests that IPR disclose the reason they investigated the 12 cases that were not protest-related, publish that information and make it available on the dashboard.

Non-Disciplinary Complaints: The option for lower-level misconduct to be investigated by an officer's direct manager rather than by IA or IPR was added in 2018. These "Supervisory Investigations" (SIs) have different possible outcomes from full investigations-- only "Substantiated" or "Not Substantiated." While the Report shows that two protest cases were handled as SIs, it only indicates that 11% of cases (presumably 34) were handled this way (appendix p. 3). PCW has always had concerns since these Non-Disciplinary Complaints (NDCs) were called "Service Complaints" that they are used to minimize community concerns. However the 11% figure for 2020 is far below the five year average of 18% being handled as NDCs, so maybe more complaints are being taken seriously.

Dismissals vs. Investigations: IPR notes that their dismissal rate went up from 42% in 2019 to 47% in 2020. PCW previously put forward that one reason this rate fell from 55% or more cases being dismissed is that IPR began referring more cases to precincts for informational purposes. We believe this happened in 43 cases in 2020 (13% per appendix p. 3). Thus, cases that were not investigated were actually about 60% this year (47%+13%), roughly 200 in total.+x With just one case sent to Mediation between the officer and complainant, this means between full investigations and Supervisory Investigations, just under 40% of cases were actually investigated in any way. (More details on Dismissals below.)

How Likely Your Case Will Be Investigated: Since most people filing complaints expect that their case will receive a full investigation with findings, looking at IPR's report, as usual, gives a person an inflated idea of the likelihood that will happen. A 47% dismissal rate implies about a 1 in 2 chance of an investigation. However, only including those cases fully investigated by IPR or IA, 27% of complaints were investigated, meaning only slightly more than 1 in 4 complainants will receive the full treatment. This is roughly the same as 2018. These odds, PCW has noted before, improved after IPR was required to investigate all Force complaints in 2014 (when the odds were 1 in 10 or worse).

Lawsuits, Disappeared: In June 2021, the CRC heard a case about a woman who notified the City of her intent to sue after police arrested her for disorderly conduct when she was twerking (and flipping off officers) in a bike lane during a 2019 protest. Her 2020 tort claim notice was used by IPR to open an investigation. Though IPR has been examining lawsuits and tort claims for years to see if allegations required investigating, there are no data as to how often that happened in 2020 (nor were there any noted in 2018 or 2019).

Mediation at a Minimum: To be fair, holding sit-down sessions between officers and complainants with professional mediators would not be an easy task under the pandemic. The one mediation in 2020 was far below the average of 7 per year from 2015-2019.+x IPR notes that one of their goals was to conduct more mediations, but were unable to do more than the one (p. 6).

CIVILIAN INVESTIGATION DOES NOT IMPROVE CASE OUTCOMES

Fewer Sustained Cases: PCW is a huge supporter of civilian-run accountability systems to avoid having police investigate other police. As the City gears up to implement the new oversight system, it's important to examine whether IPR's investigations led to significantly different outcomes than Internal Affairs. While most complainants likely prefer not having to talk to the agency they believe caused them harm, IPR's investigations may lack the strength expected, in part because IPR has to go through IA to compel officer testimony and, as of 2020, has to make public records requests to obtain documents. According to the dashboard, IPR has investigated 153 allegations of Force since 2013 and only one has been Sustained, a 0.7% rate. In the same time, Internal Affairs investigated 521 Force allegations, of which 12 were Sustained, a 2.4% rate, over three times higher than IPR's.+x Including all kinds of investigations, IPR looked at 547 allegations involving community members and 42 were Sustained-- 7.7%, while IA covered 1552 community allegations of which 13.1% (204) were Sustained.+x PCW encourages community members to look deeply at how outcomes of civilian investigations can be improved.

COMMUNITY COMMITTEE ACTIVITY INCORRECTLY REPORTED... AGAIN

Just Can't Get It Right: IPR has now flubbed their narrative about the activities of the civilian review body attached to their office, the Citizen Review Committee, four years in a row. That sad consistency shows that IPR doesn't give enough attention to the community members reviewing cases upon appeal, arguably the most transparent part of Portland's current accountability system. Generally, IPR is wrong in saying that the Committee heard appeals of three cases in 2020: technically, they only heard two cases on appeal. Here is what IPR claims happened (which to be fair is mostly correct) with the detailed information:

(A) "[CRC] challenged a finding in one [case], recommending that the supervisor change the result from unfounded to not sustained. The Chief agreed with the Committee's recommendation in that case." This was case 2020-x-0001, in which the appellant accused officers of excessive force when taking him into custody. He was incarcerated and unable to attend the appeal hearing in September. He had phoned into the Case File Review in January, at which time CRC asked for more investigation to determine which officer had effected his arrest. Because that was unable to be determined, CRC indeed voted 4-2 to change the finding to "Not Sustained," meaning there wasn't enough evidence to prove or disprove what happened.

(B) "In [another] case, the Committee affirmed one finding, challenged two, and asked for more information on a fourth allegation." This is also accurate, as the appellant in case 2020-x-0002, former PPB Sergeant Liani Reyna, asked that CRC change two "Exonerated" (in policy) findings about the Commander and Captain of Internal Affairs not handling her earlier complaint properly. The Bureau found the two other allegations, that the officers' actions were retaliatory, "Unfounded" (meaning the evidence doesn't support that the action happened at all). CRC voted 4-1 to change both Retaliation findings to "Not Sustained with a debriefing" in part based on Sgt. Reyna's protected classifications as a woman, a Latina, a lesbian, and a whistleblower. They also voted 4-1 to accept the Exonerated finding for the Captain about process, since PPB policy at the time did not require them to inform her of the outcome of a separate complaint she'd filed while still at the Bureau-- only civilians had that privilege at the time. The quaintly phrased "asked for more information on a fourth allegation" doesn't capture that IPR and Internal Affairs must re-investigate what CRC asks them to, per City Code changed after the DOJ Agreement required it.*-3 However, that hearing was in October and as of late June, 2021 the case has not come back with information the CRC requested about why the Commander refused to investigate Reyna's allegations of untruthfulness against another officer.

(C) "The Chief disagreed with the Committee's recommendation in another case, which eventually was heard by City Council. Council sided with the Committee's recommendation." This reporting reflects the difficulty of breaking down governmental activities by calendar year, especially in such a slow-moving system. In our analysis of the 2019 IPR Annual Report, PCW wrote about this case, 2019-x-0003, heard in December 2019. A woman said an officer failed to take a report about her stolen car complaint, leading to her being unable to recover it (or prosecute the criminal). At the time, CRC voted 4-2 to recommend a "Sustained" finding. The meeting held in August 2020 was a Conference Hearing at which Chief Lovell tried to get CRC to agree to a "Not Sustained with a debriefing" finding. (Notably, Danielle Outlaw was Chief at the time of the first hearing, and Jami Resch took over from January to June 2021.) CRC voted again, 6-2, to send the case back to the PPB for a "Sustained" finding based on language in the policy saying the officer should have either accepted her in-process paperwork from the DMV or called a supervisor to approve a report. Lovell said he would order more investigation, rather than send the case to City Council as required by ordinance. But the only follow-up was another interview with the officer, not, as promised, verification of the paperwork the Appellant had presented to CRC. In February 2021, CRC held a second conference hearing and sent the case back again on a 6-1 vote, leading to a City Council hearing (not identified by IPR as being in April 2021). Council voted 4-0 to support the "Sustained" finding-- only the second such action by Council in the 19 years of CRC and the first to be unanimous and include the Mayor/Police Commissioner.*-4

Committee Pushes Back at Higher-than-Usual Rate: IPR's section heading for CRC is "Citizen Review Committee Challenges Police Supervisor's Positions." It is true that in the three cases CRC heard in 2021, including at the Conference Hearing, they sent back four findings, accepted one and sent one back for more investigation-- meaning they only agreed with the Bureau once, or 16% of the time. In 2018 that figure was 63%. However, of the four challenged findings, only one was recommended to be "Sustained" (eventually accepted by Council), while the other three were changing non-sustained findings from Unfounded to Not Sustained. So from a community point of view, they also were only able to fully support a complainant 16% of the time. +x

One Work Group Mentioned: Last year, IPR mentioned CRC's work groups, but not specific actions such as the CRC's forum on Crowd Control that year. This year they say CRC (not its Crowd Control Work Group) "worked on a crowd control report for release in 2021." No mention that the Work Group held a community forum in July 2020, then took a public survey in September. The Work Group report is indeed expected to be published this year. CRC's Policy and Outreach Work Group also met a few times, but to be fair that only happened in 2021.

No Mention of Limited Power and Member Resignations: IPR does not mention the limiting "standard of review" by which CRC and Council must determine whether a reasonable person given the evidence could come to the same finding as the Bureau. This limitation-- and the Auditor's office failing to support CRC's request to change it-- led directly or indirectly to the resignations of four CRC members in a year: former Chair Kristin Malone (in February 2020), former "Recorder" Daniel Schwartz (technically in December 2019), and members Heather Hafner and Adam Greene in September 2020. (A fifth member, Carol Johnson, left the state and also resigned in September.) In all, out of 78 CRC members seated in the nearly 20 years since October 2001, 43 (56%) have resigned, at least two per year. More accurately, that is 64% of people who have left the board, since there are currently 11 members still seated.+x

CRC Minimized Again: The CRC used to have an entire chapter in the longer reports which listed the names of the members, all of the Work Groups, and their activities. This year's report only states that CRC "released a statement in response to the killing of George Floyd... held recurring meetings with elected officials, and the Chair participated in monthly meetings with the chairs of different advisory councils."

Dismissal Appeal Process: In the past, complainants whose cases were dismissed by IPR were allowed to "protest" the decision by having another staff person look at the complaint for reconsideration. Data on how often--and whether-- that happens has not been included in a Report since 2015.

WHY COMPLAINTS WERE DISMISSED

Thinking Outside the Box: As noted in our 2018 analysis, City Code 3.21.120(C)(4) lists only eight reasons IPR can dismiss cases, but IPR uses more than that. When PCW called this out in an analysis of the Bureau's Directives (policies), the Bureau responded that IPR included the categories "complainant not reliable or credible" and "too vague" in its administrative rules. It's not clear whether either of these are the same as "Lack of Investigative Merit," which IPR lists as one of the reasons it dismissed cases in 2019 and 2020.+x

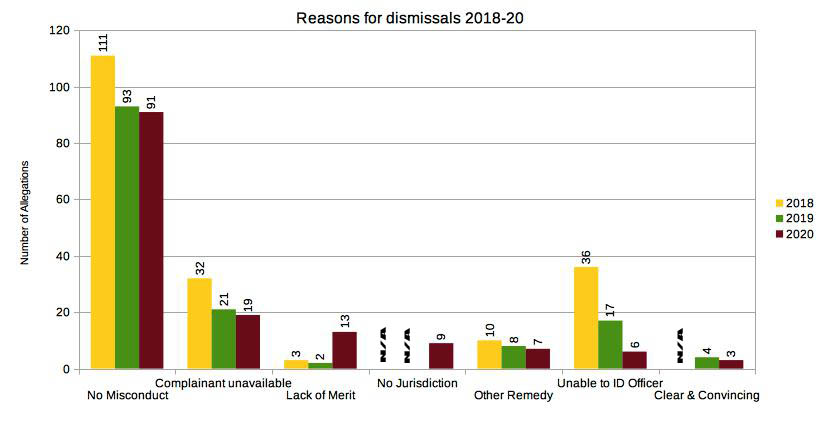

How Often Allegations Dismissed: The 2020 Report has two figures showing why cases were dismissed. The first, on p. 3, only addresses protest cases. The second, on appendix page 4, only gives figures as percentages. Here is PCW's inclusion of what we believe are the raw numbers as well; the numbers here are derived from the Report and do not all match the dashboard; the one exception is the "third party complaint," which is also not part of City Code, that isn't listed in the Report. As noted above, though the only category supposed to be used to dismiss Force complaints is "Clear and Convincing Evidence," none of the dropped Force cases used that criterion. It is not clear why "Lack of Investigative Merit" jumped from less than 2% of dismissals to 9% in 2020. It's also interesting that the inability to identify officers-- a huge problem due to officers not wearing name tags during the protests-- went down considerably from 2018 and 2019.

--No Misconduct: 61% of dismissals, estimated 91 times;

this was used in 63% of dismissals/93 times in 2019 and 55%/111 times in

2018.

--Complainant unavailable or withdrawn: 13% of dismissals, estimated 19 times;

this was used in 14% of dismissals/21 times in 2019 and 16%/32 times in 2018.

--Lack of Investigative Merit: Category not in the ordinance, used 9% of the time, estimated 13

times;

this was used in just 1% of dismissals/2 times in 2019 and 1.5%/3 times in 2018.

--No Jurisdiction: 6% of dismissals, estimated 9 times;

we can't find evidence this was used in previous years.

--Judicial or Other Remedy (eg, could be resolved in court): 5% of dismissals, estimated 7

times;

this was also used 5% of the time in 2019 (8 cases) and 2018 (10 cases).

This has been used more than 150 times over 10 years to dismiss

complaints.

PCW has noted before that if a person challenges a ticket,

that doesn't hold the officer accountable for misconduct.

--Unable to Identify Officer: 4% of dismissals, estimated 6 times;

this was used in 11% of dismissals/17 times in 2019 and 18%/36 times in 2018

--Clear and Convincing Evidence: 2% of dismissals, estimated 3 times;

this was first reported used in 2019 for 3% of dismissals, 4 times.

As with 2020, none of those were for Force cases.

We have also included these data as a chart at https://www.pjw.info/copwatch/IPR_annual2020/dismissals2020.jpg .

Who's Monitoring Case Decisions?: Although the Compliance Officer/Community Liaison (COCL) examines random samples of IPR cases to ensure investigative findings match the evidence, it's not clear that they dig deeply into dismissals to ensure they are being done properly. The CRC has a Recurring Audit Work Group which in 2019 conceived of reviewing dismissals as part of a broader review of IPR case handling, but that never moved past the conceptual stage. This followed the previous iteration of that Work Group preparing to report on dismissals between 2011 and 2018, but never finishing their project.

POLICE-ON-POLICE MISCONDUCT MORE OFTEN LEADS TO GUILTY FINDINGS

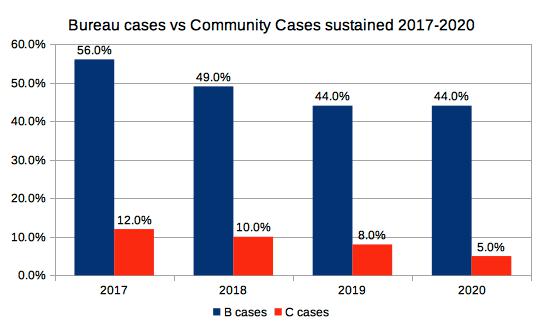

More Cops Found to Commit Internal Violations: IPR's Report notes twice that there were 66 misconduct complaints that came from inside the Bureau (p. 2 and appendix p. 1), and comments this is about the same number as in 2019 (69). In the appendix, IPR notes the percentage of allegations Sustained in these so-called "B" cases (Bureau only, no community member involvement... allegedly*-5) is 44%, the same, they say, as in 2019.*-6 There is no analysis why this is so much higher than the 5% of investigated community allegations that are Sustained. For the record, IPR's numbers over four years for Sustained "B" cases is 56%-49%-44%-44%, while community rates were 12%-10%-8%-5%. We made a visual for this information at https://www.pjw.info/copwatch/IPR_annual2020/sustain_rates_ipr2020.jpg.

True for Non-Disciplinary Cases Too: IPR does not include any detailed current data on Supervisory Investigations. PCW finds that Cop-on-Cop complaints are treated as even more believable in this area than for disciplinary investigations. In 2020, 12 of 15 Bureau-on-Bureau SI's were "substantiated" (80%) whereas civilians' complaints only resulted in 7 of 47 allegations being "substantiated" (15%). Overall in the three years SI's have been used and tracked, 19 of 25 Bureau allegations were found to be true while only 28 of 273 civilian allegations were supported. That's a nearly 8:1 difference when Supervisors are reviewing complaints instead of the civilian oversight agency or even Internal Affairs-- 76% vs 10%.+x

ANALYSIS OF NON-SUSTAINED FINDINGS

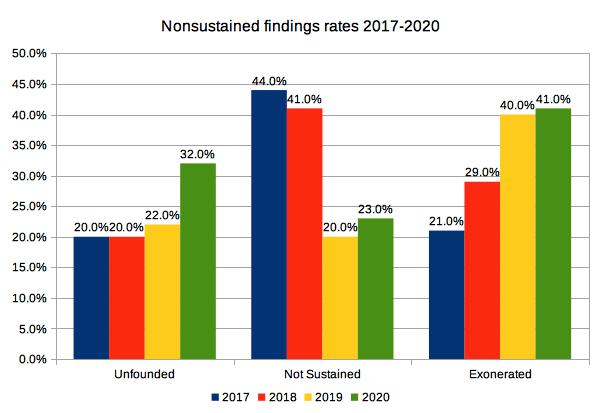

In Policy/Can't Tell/Didn't Happen: The possible findings other than "Sustained" are "Exonerated" (action was in policy), "Not Sustained" (insufficient evidence) and "Unfounded" (evidence shows alleged action did not happen). PCW has noted in the past how many investigations hinge on the word of just two people: the complainant and the officer, and thus most non-sustained findings should be "Not Sustained." In the last few years, the Bureau has been using "Unfounded" in increasing numbers, which is made worse by their current definition which calls the allegations "false or without a credible basis as a possible violation of Bureau policy or procedures" instead of the 2007 definition of "the available facts of the investigation do not support the allegation." IPR shows that 32% of community allegations were called "Unfounded" in 2019 and 2020, way up from 22% and 20% in 2017-2018. "Not Sustained" was only used in 23% of findings in 2020, up from 20% but far lower than 41% in 2018 and 44% in 2017. Exonerated findings, on the other hand, have tended upward, with 41% of findings in 2020 and 40% in 2019 compared to 29% in 2018 and 21% in 2017. See our chart at https://www.pjw.info/copwatch/IPR_annual2020/nonsustained_findings2020.jpg .

Did They Get Talked to About Their Conduct?: Sustained findings lead to some kind of discipline, whether Command Counseling, a Letter of Reprimand, time off without pay, a demotion or termination. The non-sustained findings can all have a "debriefing" attached to them, but IPR does not report on these important supervisor-officer discussions anywhere-- not in the Report, not on the dashboard, not in its monthly reports. It seems as if the IPR does not value debriefings. A case heard by CRC in June 2021 included allegations of improper arrest and racial profiling. IPR staff claimed they were not happy about the incident but found the officers' actions mostly within policy or at least hard to prove as infractions. Yet the CRC ended up adding debriefings to every finding, raising the question of why, if IPR found the incident was not handled well, they did not propose that themselves.

DIGGING INTO DISCIPLINE DATA

Comparing Outcomes Difficult: IPR reports on the total number of instances where discipline was imposed, but does not differentiate whether those were the results of community or Bureau complaints. It also makes no connection between what kinds of misconduct led to the disciplinary actions. The Report lists 20 times discipline was imposed and that three officers resigned or retired before getting punished. That total of 23 cases is less than the 32 in 2019 or 26 from 2018. The data are also confusing since IPR says there were 45 Sustained allegations (35 Bureau/10 Community), which could have only been attached to 23 cases but there's no way to know.

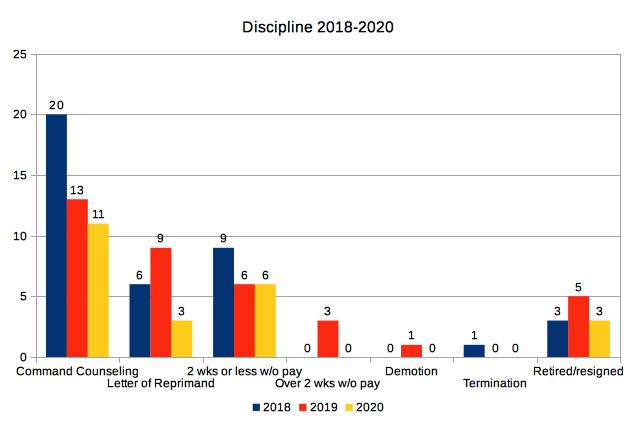

What Happened to Cops: IPR's numbers in the last three years have shown no officers terminated since 2018, one demoted in 2019, and only three receiving more than two weeks off without pay (all in 2019). This year, six had two weeks or less off without pay (same as 2019, fewer than the 9 in 2018), three received Letters of Reprimand (down from 9 in 2019 and 6 in 2018), and 11 received Command Counseling (also down from 13 in 2019 and 20 in 2018). Officers who resigned/retired was 3 in 2020 (as it was in 2018), and 5 in 2019. We mapped out these three years in a chart at https://www.pjw.info/copwatch/IPR_annual2020/discipline2020.jpg .

Invisible Process to Discipline: The only mention of the Bureau's Police Review Board (PRB) is in the chart on appendix p. 1 showing which parts of the oversight system have what authority. This is particularly remarkable since IPR (a) has voting membership on every PRB hearing held, (b) recruits and nominates the pool of community members who rotate into a voting seat, and (c) manages the Citizen Review Committee, which gets to have one member on PRBs that look at deadly force and other serious cases. For a little while, IPR used to include information about the number of PRB hearings and their outcomes. While Portland Copwatch analyzes PRB semi-annual reports for data, because the year of the complaint, year of the finding, and year the PRB reports are published might all differ, we are choosing not to attempt a comparison here.

Other PRB Shortcomings: The Annual Report should also indicate how often the Chief and/or Police Commissioner agreed with the PRB's proposed findings and track the many recommendations made by the PRB. IPR does not include any of this information.

IPR EVEN LIMITS REPORTING ON ITSELF

Policy Vagaries: IPR does mention the existence of its own recommendations around Transit Police and flashlights on firearms, but doesn't say much about them (pp. 5-6). The Transit Division report "found that accountabliity falls short of community expectations," they said, and that the PPB stopped managing Tri-Met security shortly after the report came out. This leaves the reader with an impression that there was a cause and effect between the report and the dissolution, when in fact the City defunded the Transit Division as part of the budget cuts demanded after the death of George Floyd (the Gun Violence Reduction Team and School Police were also cut). The flashlight report summary does state that IPR recommended "more specific policies and trainings on the types of flashlights allowed," which is closer to a summary than anything from IPR in recent years. The PDF of the Report provides hyperlinks, which are not helpful when one prints the Report.

Outreach to Nowhere?: While it is true that 2020 was a very difficult year to get out and about in the community, IPR does have an Outreach coordinator whose activities are usually summarized in the IPR Director's monthly reports. PCW has had concerns that previous Outreach sections in Annual Reports were little more than lists of organizations contacted, but it is strange that this activity is not even mentioned-- in fact, a word search shows the word "outreach" is not in the 2020 Report. At the very least, the staff should be given some credit for recruiting volunteers for the CRC and the Police Review Board.

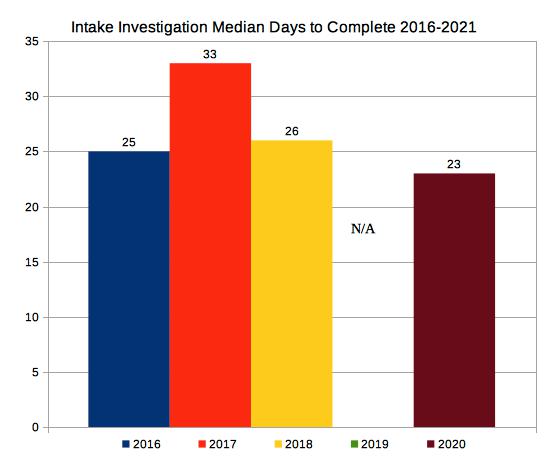

Timeliness: IPR used to include detailed data tables on the timeliness of investigations, showing their intake process, the investigations, supervisory review and other elements to break down how and whether complaints were being closed in 180 days as required by the US DOJ Agreement. The first data point about timeliness is in an infograhpic on p. 2, showing intake investigations now take a median of 23 days. Previous iterations would show if this was an increase or not; the 2018 report showed that time was down to 26 days, for example. That timeline was 25 days in 2016, 33 days in 2017, and no figure was given for 2019.+x The second piece of information is in a section on p. 5 about how "untimely investigations affect compliance with settlement agreement," noting that "up to 83 percent of IPR's investigations went over the allotted 180 days in the first, second and third quarters of 2020." There is no information on Q4. Compare the provided data on intake at https://www.pjw.info/copwatch/IPR_annual2020/intake_investigations2020.jpg .

...BUT ALSO SPENDS TIME EXPLAINING SHORTCOMINGS

Don't Look at the Institution: Nearly half of the Report is about how the system was overloaded and inadequate to address the surge in complaints during the social justice uprising in 2020. The summary on p. 1 references that the system was "overwhelmed." Nearly all of p. 4 explains how an "increase in complaints strained investigative capacity," which leads to a graphic on p. 5 showing the workload for IA and IPR, followed by a kindly warning to people with high expectations that "misconduct investigations alone can't fix policing." This last section notes that officer actions often don't necessarily violate policy, leading to community members becoming "frustrated or confused." They say that IPR looks for trends to fix policies, leading into their summaries of the aforementioned policy reviews. Were flashlights on guns and the Transit Police the highest priority issues of community concern? And did IPR's recommendations lead to any changes? Here's to hoping that in the next two years while IPR and CRC still exist, the paid staff will reach out to the community for assistance in identifying issues for review and in writing these reports, as the city moves toward its new system of oversight where the community members will actually be hiring the new Director.

Elusive Goals: IPR uses most of p. 6 to highlight some of its stated goals and give updates. While some, including the reference to the Michael Fesser investigation, are specific, others are more vague. As noted above, IPR says they are analyzing data on Disparate Treatment, traffic and pedestrian stops, and Use of Force but has no timeline on when their findings will be made public (and no indication they plan to involve the community in the discussion). They talk about how the single case sent to mediation was a setback due to COVID, when they want to promote that program. There are references to the limits of how much information IPR is allowed to share and access. The Report says the Auditor is trying to fix the issues at the legislature, but does not list any specific legislation, so it's difficult to know if it relates to anything that happened in the 2021 session. Finally IPR says they received "Results-Based Accountability training" and used it to "revamp" their equity training and add "root-cause analysis" into their work. None of these really explain what these changes were about. They say this led to more of an "outcomes-based approach," which is ironic given how little information and attention are given to outcomes in this and other IPR-generated reports.

WHAT'S THIS ALL ABOUT, ANYWAY?

No Human Element: Broadly speaking, people want to know what police are accused of doing, what the investigations found and what, if any, resulting actions took place. With minimal numbers and data, the IPR Report only tangentially talks about two incidents: the Portland officers involved in the racially motivated arrest of Michael Fesser on behalf of West Linn police (though the Report doesn't note that IPR found no PPB wrongdoing) and "a complaint where an officer used the flashlight on his gun to look into and clear an unoccupied tent" (which led to the flashlight policy review). In the past, IPR used to include at least one case summary in each section to illustrate what kinds of conduct was investigated. Sometime in the past two years, as we noted in our last analysis, IPR created a dashboard including case samples.*-7 They do not include the year the incident happened, whether a case was appealed to the Citizen Review Committee (at least one was), or what discipline was applied if the officer was found out of policy.

Sample the Finest Example: To illustrate the vagueness of the online narratives, PCW has transcribed the sample Supervisory Investigation given online:

"A community member contacted IPR to report concerns about

a Police Bureau SUV driving in a manner that was of concern.

The community member reported they saw the vehicle make

two turns at intersections without using a turn signal. The community

member expressed concern that officers should be modeling good

behavior when driving in Portland.""Resolution: The supervisor of the officer who was driving the vehicle

contacted the complainant to confirm details of the allegation. The

supervisor then contacted both officers working in the vehicle to find out

who was driving and hear their recollections. At the end of the investigation,

the supervisor concluded the allegations were were [sic] supported by the evidence."

So, it is not even clear whether the above typo ("were were") suggests the finding was "Substantiated" (if the second "were" is accidental) or "Not Substantiated" (if the second "were" is supposed to say "not). Putting the actual finding in the narrative would clear this up.

CONCLUSION

As we suggested in 2018 (and elsewhere), IPR should consider their Annual Reports important tools for community members concerned with police conduct and accountability, as well as for researchers both within Portland and from around the country. We note again that Eugene's police review agency, which has a much smaller staff and caseload, has more details in its 14-page report than IPR's. Eugene's 2019 report also includes a detailed summary of every major and minor complaint they processed in 57 pages of appendices.*-8 Washington, DC's review board put out a 27-page report with a six page appendix including tables mapping certain kinds of allegations to the resulting discipline.*-9 Looking to Eugene, it would seem IPR's excuses about the limits of state law are overstated; looking to DC, it seems that board is more interested in communicating key information to the public.

Just as important as the depth and breadth of the Report is to involve the community in its creation and distribution. The Citizen Review Committee used to at least be asked to review the chapter about their activities and receive a presentation by staff of the finished report at a public meeting. Reports also used to be presented to City Council, and the public was allowed to make comments in both spaces. Residents of Portland should not have to wait for the new oversight system to be in place for such improvements to take place.

In a year following the mantra that "Black Lives Matter," it is unconscionable that we still have a system that has only Sustained one Disparate Treatment allegation in 20 years, continues to rarely Sustain Force complaints, and barely discusses when community members are shot, shot at or killed in custody. Although neither Grey Stockton nor David Dahlen, each shot at by the PPB, was a person of color, Stockton lives with some form of disability. The PPB's Force reports break out data about people with mental health issues, IPR should as well.

This year's Copwatch analysis of the IPR's 13 page Report is 11 pages long*-10 because we want to get more information to the community than is being shared by our self-described transparent oversight system. After our initial analysis of the 2019 Report last June, we began a more detailed document which ended up getting set aside as people rose up for racial justice and an end to police impunity. Volunteer community members should not have to work so hard. We hope IPR will step up and create a good example for the review board that follows them.

footnotes

*1-

https://www.portland.gov/sites/default/files/2021/2020-annual-report-and-appendix_0.pdf

*2- 2020 Use of Force Data can be found at

https://www.portlandoregon.gov/police/80863 .

*4- We will include this case again in our analysis of the 2021 Annual Report.

*5- see PCW's analyses of Police Review Board reports on how often B cases do involve

community members at

https://www.portlandcopwatch.org/shootings.html#background .

*6-: However when PCW checked the data last year, it was 22 of 102 investigated allegations or

22% Sustained; now it shows 35 of 133 allegations which is only 26%.

*7-

https://www.portlandoregon.gov/ipr/article/760510

*8- Eugene 2019 report:

https://eugene-or.gov/ArchiveCenter/ViewFile/Item/5846

*9- DC 2020 report:

https://policecomplaints.dc.gov/sites/default/files/dc/sites/office%20of%20police%20complaints/pu

blication/attachments/2020%20Annual%20Report_Final.pdf

*10-without the graphics included this analysis is 11 pages, with them it is about 14 pages.

Posted June 28, 2020, last updated November 15, 2021